Time Will Tell If Elevated Dry Powder Levels Will Be Good or Bad For LPs

March 7, 2024

.jpeg)

Today’s Chart of the Week focuses on the private equity industry, specifically examining the concept of dry powder. In the world of private equity, dry powder (or overhang) refers to the amount of committed, but un-invested capital that a private equity firm has at its disposal. This capital is raised from institutional investors such as pension funds, endowments and sovereign wealth funds — or high net worth individuals who entrust the private equity firm to invest wisely into promising companies. Dry powder is essentially the fuel that powers private equity deals.

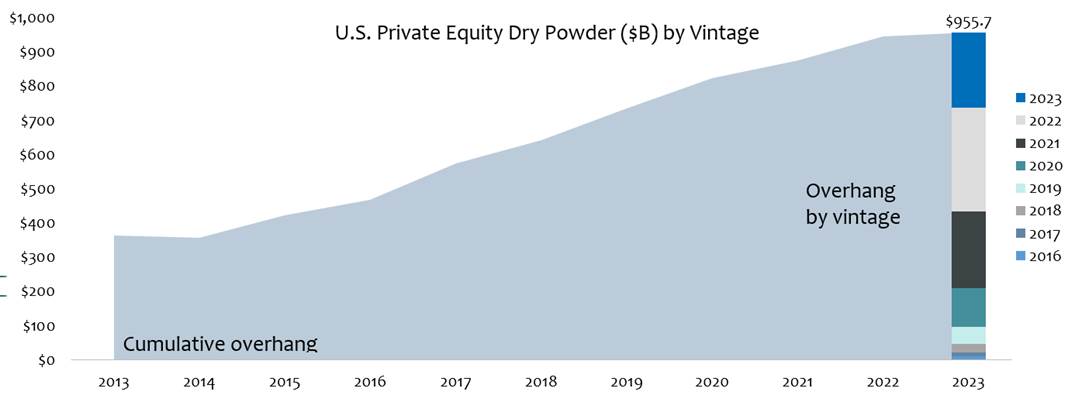

Over the past several years, dry powder levels in the private equity industry have reached unprecedented heights. This is due to a combination of factors, including a continued strong private equity fundraising environment, increasing investor appetite for alternative assets, fewer options to put that capital to work on attractive terms and a more cautious investment environment brought on by economic uncertainty. These factors have combined to result in a record high U.S. private equity capital overhang of nearly $1 trillion as of March 31, 20231 — double what it was just over five years ago.

Dry powder serves several strategic purposes for private equity firms, including:

- Opportunistic Investing: Dry powder gives private equity firms the flexibility to act quickly and decisively when promising investment opportunities arise, especially in down markets or periods of distress. They can capitalize on situations where valuations are attractive or competitors are hesitant.

- Competitive Advantage: Firms with substantial dry powder hold strong negotiating power, potentially securing more favorable deal terms. This can lead to higher potential returns.

- Portfolio Company Support: Dry powder can be used to support existing portfolio companies during economic downturns, helping them weather challenges or even take advantage of strategic growth opportunities.

- Attractiveness to Investors: Large dry powder reserves can signal a private equity firm's strength and deal-making potential to prospective investors who are seeking to allocate their own capital. This can be a deciding factor when investors are comparing funds.

- Potential for Deal Flow: Ample dry powder can attract sellers who may be drawn to the certainty of a firm that has the resources to close transactions quickly.

While ample dry powder has benefits, excess dry powder has the potential to present such challenges as:

- Pressure to Deploy: As dry powder piles up, general partners (GPs) may feel mounting pressure to find suitable investments, potentially leading to rushed decisions and overpaying for acquisitions. This can result in lower returns for limited partners (LPs).

- Artificially Inflated Valuations: Abundant dry powder fuels fierce competition for the most attractive assets. This bidding war can drive up valuations, making it harder for GPs to secure deals that will generate their target returns.

- Reduced Deal Discipline: In a highly competitive environment, some GPs might compromise on their investment criteria, taking on riskier targets or accepting less favorable deal structures.

- Potential for Misallocation: If too much capital chases limited opportunities, resources could be directed toward subpar companies or sectors, harming fund returns.

- Management Fee Implications: GPs often charge investors management fees as a percentage of total committed capital, even if it has not yet been invested. Therefore, excess dry powder may cause investors to pay for capital that may not be actively generating returns.

Key Takeaway

Dry powder is a critical resource for private equity firms, empowering them to act decisively and weather market fluctuations. The abundance of dry powder in the private equity landscape underscores the resilience of the asset class and investor confidence in the ability of experienced GPs to generate returns. However, it necessitates a disciplined investment approach. To succeed in the long run, private equity firms must strike a balance between deploying capital strategically and maintaining the flexibility to capitalize on future investment opportunities.

Note:

1Private equity data typically has a 6-month lag or so given the type of investing.

Definition:

Vintage year refers to the milestone year in which the first influx of investment capital is delivered to a project or company, marking the moment when capital is committed.

This material is for informational use only. The views expressed are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Penn Mutual Asset Management. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research or investment advice, and it is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy.

Opinions and statements of financial market trends that are based on current market conditions constitute judgment of the author and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained in this material are derived from sources deemed to be reliable but should not be assumed to be accurate or complete. Statements that reflect projections or expectations of future financial or economic performance of the markets may be considered forward-looking statements. Actual results may differ significantly. Any forecasts contained in this material are based on various estimates and assumptions, and there can be no assurance that such estimates or assumptions will prove accurate.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All information referenced in preparation of this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy and completeness are not guaranteed. There is no representation or warranty as to the accuracy of the information and Penn Mutual Asset Management shall have no liability for decisions based upon such information.

High-Yield bonds are subject to greater fluctuations in value and risk of loss of income and principal. Investing in higher yielding, lower rated corporate bonds have a greater risk of price fluctuations and loss of principal and income than U.S. Treasury bonds and bills. Government securities offer a higher degree of safety and are guaranteed as to the timely payment of principal and interest if held to maturity.

All trademarks are the property of their respective owners. This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission.